We all know sex tends to decline with age; that’s nothing new. But what’s happening now is different.

Couples today are having far less sex than couples the same age just a generation ago⁽¹⁾. What used to be once a week has fallen to once or twice a month, and for many, none at all⁽²⁾. And this isn’t just a bedroom issue because when sex disappears, relationships weaken, health suffers, families struggle, and the consequences for society are significant⁽³⁾.

So, in this article, I want to look at what’s really going on, why marital sex is declining so fast, and why it matters.

How Common Are Sexless Marriages Today?

You’ve probably heard the stat that 1 in 5 marriages are “sexless.”⁽⁴⁾ That often gets taken to mean the other 4 in 5 couples are having plenty of sex. But that’s obviously not true because the stat only counts the most extreme cases where couples are having sex fewer than ten times a year. So if you’re having sex once a month, you don’t even appear in that statistic.

And just to be clear: in research, ‘sexless’ doesn’t mean zero sex, it’s just a technical definition⁽⁵⁾. But let’s be honest: once a month would still feel like a sexless marriage to most. Try asking 100 married middle-aged men how great their sex life is and you’ll get an awkward silence from a lot more than 1 in 5 of them.

And the stats back this up.

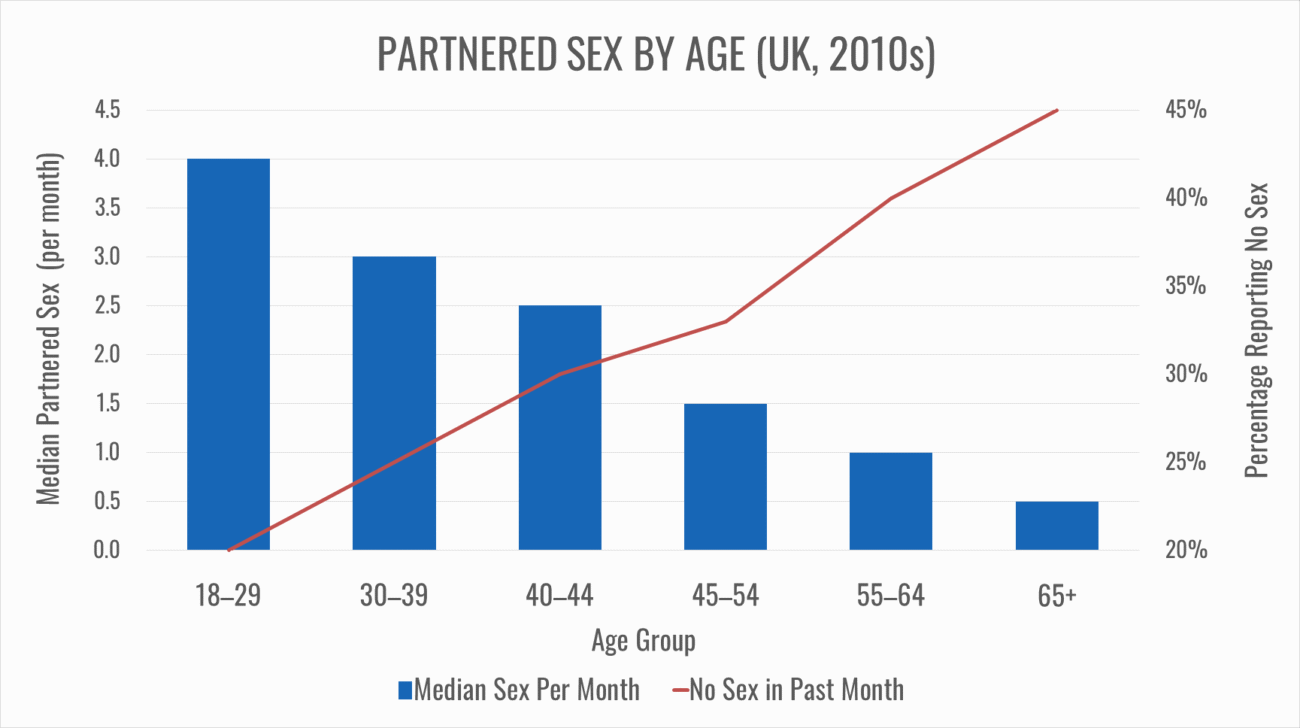

Sources: Natsal-3 (2010–12), Britain’s probability survey of sexual behaviour and lifestyles [G1]; YouGov UK polling on sexual frequency (2020) [G2].

The British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles found that by ages 35–44, couples were averaging 2–3 times per month. By 45–54 it drops again, often to once or twice a month and about 1 in 3 report no sex at all. Nothing. Zilch. Nada⁽⁶⁾.

And remember, these numbers are probably conservative because people feel embarrassed talking about sex, especially us Brits, so we tend to give rosier answers⁽⁷⁾. The true extent of sexless marriages is likely far worse. Just bear that in mind the next time someone cuts you off in traffic.

How Does Today Compare to a Generation Ago?

We all know the 90s were better, the culture, the fun, the freedom. Well, it turns out, the stats agree, at least when it comes to sex⁽⁸⁾.

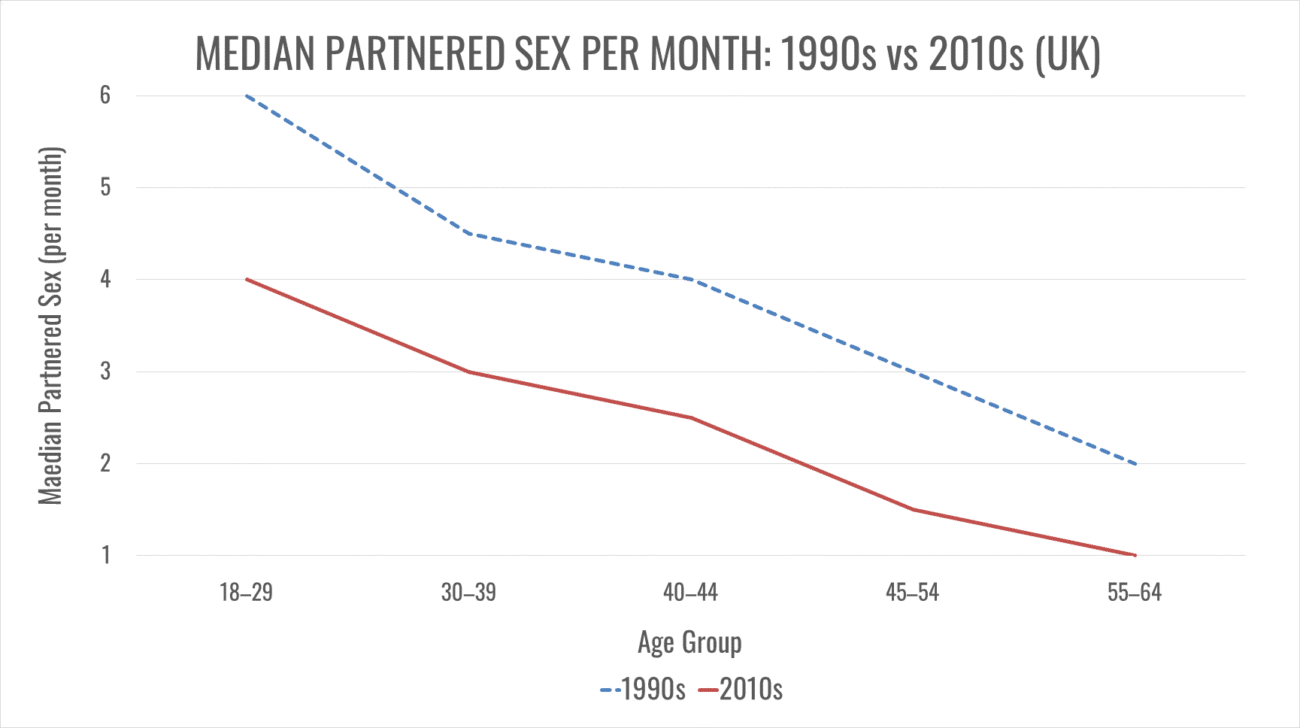

Sources: Natsal-2 (1999–2001) and Natsal-3 (2010–12) comparative analyses of sexual frequency in Britain [G3], [G1].

Back then, people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s were having way more sex. By the 2010s, frequent sex more than halved in the 35–44 age group⁽⁸⁾.

And it’s not just the UK. Studies from the US, Australia, and Nordic countries show the same thing: partnered sex has dropped by 15–28% per decade since the early 2000s⁽⁹⁾.

Zoom out even further, and here’s the long-term trend:

Sources: Natsal-3 summary metrics for partnered sexual frequency in Britain [G1]; long-run decline context from population studies of sexual frequency (1989–2014) [G4].

For most of the 20th century, couples held steady at about once a week, but since the 1990s, it’s plummeted to just 2–3 times a month⁽¹⁰⁾. The long plateau followed by a sharp decline shows just how unusual and recent this shift really is.

Why Is Sexual Frequency Declining?

In the 90s and before, people went out more. Pubs, clubs, social gatherings, and most people worked face-to-face. That social engagement led to far more opportunities to form relationships⁽¹¹⁾. Today, our more isolated existence means it’s harder than ever to even form a committed relationship.

And for those who do manage to establish long-term bonds, the pace of modern life can be brutal. Couples juggle jobs, kids, bills, and endless to-do lists. And unlike in the past, both partners usually work full-time and share the domestic load⁽¹²⁾. Many couples collapse into bed after half a bottle of wine, glued to phones, wondering why their sex lives are flatlining.

And speaking of phones, these little things are sucking the life out of relationships. Evenings once spent together are swallowed by Netflix, TikTok, and mindless scrolling. Couples sit in the same room, but they’re not really with each other. Just as caged animals stop mating when stripped of healthy stimulation, I suspect this digital captivity is having the same effect on us. Researchers now call digital distraction one of the biggest threats to intimacy⁽¹³⁾.

👉 What do you think? Are screens harming your relationship? Let me know in the comments.

Then there’s the high-speed, on-demand porn which has changed sexual habits and expectations. For some, rather than facing sexual problems in their relationship, they turn to porn as a substitute. But over time, that avoidance just drives couples further apart⁽¹⁴⁾.

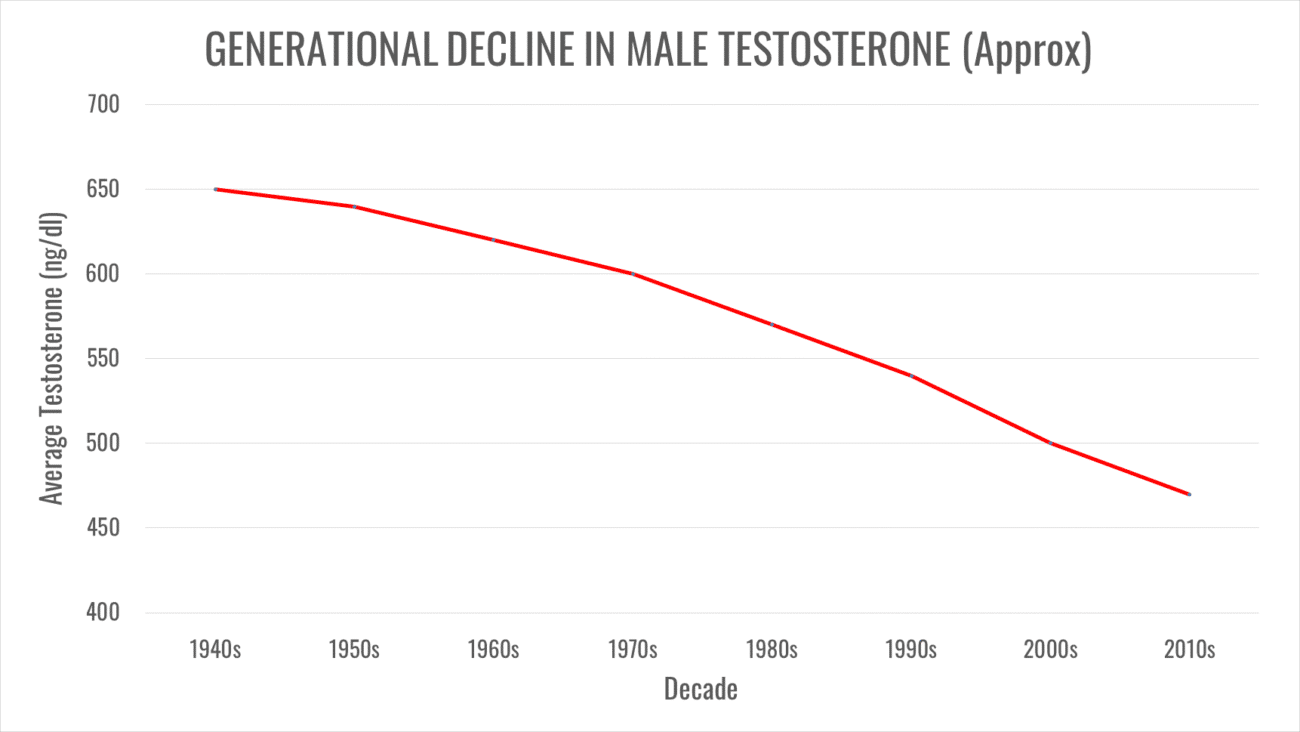

Sources: U.S. population-level decline in serum testosterone, 1987–2004 [G5]; additional secular-trend evidence from Australia and other cohorts [G6], [G7].

Another trend is that men today have lower testosterone at the same age than their fathers or grandfathers did. Causes include obesity, poor sleep, sedentary lifestyles, chronic stress, and hormone-disrupting chemicals in the environment⁽¹⁶⁾. That means men today are, on average, a little less horny, not that any of my regular readers would agree.

Sources: NHS England/BSA “Medicines Used in Mental Health” trend reports (2015/16–2021/22+) [G8]; NHS Prescription Cost Analysis time series [G9]. For U.S. context: CDC/NCHS trend in antidepressant use, 1999–2018 [G10]. Teen prescribing roughly doubling vs mid-2000s: UK child/adolescent prescribing trend analyses [G11].

The overprescribing of meds is another major factor. Antidepressant use has soared by more than a third in England since 2015⁽¹⁷⁾, and in the U.S. from about 8% in 1999 to nearly 14% by 2018⁽¹⁸⁾. Even teenagers are now prescribed them at twice the rate of the mid-2000s⁽¹⁹⁾. One of the many problems with these drugs is that they are notorious for killing libido⁽²⁰⁾.

Furthermore, in our modern culture there’s a distinct lack of a marital code or moral guidance. In the past, marriage was taken seriously, and couples were supported. Communities, extended families, even churches guided couples on how to make marriage work⁽²¹⁾. I am not saying those institutions were always positive, but for centuries there was a strong cultural acceptance that sex mattered and that neglecting it would undermine family stability. Today, those support systems have largely disappeared, and I fear we’ve thrown the baby out with the bath water because couples are more isolated than ever.

The result is that sex is now commonly dismissed as “just physical”, unnecessary even, whilst emotional connection is put on a pedestal⁽²²⁾. Of course, emotional connection matters, but the effect is that sex is no longer widely seen as the legitimate need it is.

This ties into another recent cultural shift, which is individualism. We hear endless talk about ‘putting yourself first,’ but along the way we’ve lost the language of duty, generosity, and partnership⁽²³⁾. Now, the focus is mostly on what we feel we deserve instead of what we ought to give. And nowhere is that more obvious than in how we treat each other’s sexual needs.

To make matters worse, being single is sold as one endless parade of freedom and passion, while marriage is portrayed as sexually boring⁽²⁴⁾. The research shows the opposite of course: that sex in long-term relationships is more meaningful, more satisfying, and more connecting than casual flings⁽²⁵⁾. The tragedy is that too many couples buy into the myth and then live it out as if it were inevitable.

And that’s the whole point of this blog; to show couples that marriage can be the richest and most rewarding experience in life, if you do it right.

Finally, and this is a big one… the dreaded gender war. The mistrust between men and women now is nothing short of a tragedy. Online echo chambers fuel resentment on both sides, whether it’s the red-pill crowd or hostile strands of feminism⁽²⁶⁾. They’re as bad as each other, but when it comes to marital sex, modern feminism has taken a wrecking ball to the notion that it matters at all⁽²⁷⁾. The idea that our husbands need sex on an emotional level has been ridiculed and dismissed⁽²⁸⁾. Men are often portrayed as shallow or entitled if they express sexual needs, rather than as human beings wired to connect through sex. The result is that trust feels harder than ever, and the motivation to connect, whether you’re dating or already married, is slowly evaporating.

Where Is This Heading?

If trends continue, we’re heading toward a world where not having sex in marriage is normalised⁽²⁹⁾. Where sexlessness was once considered a warning sign, it could soon be brushed off as “just the way things are.” which is highly problematic for society. Because at the couple level, even once-a-week sex is linked to greater happiness, stability, and resilience to stress⁽³⁰⁾. When its absent, resentment grows, emotional distance sets in, and the risk of divorce skyrockets⁽³¹⁾.

And on a health level, sex isn’t just a fun hobby like bowling or going to the cinema. It lowers stress, strengthens immunity, and supports emotional resilience⁽³²⁾. People who involuntarily go without end up lonely, anxious and unwell⁽³³⁾.

Children suffer too when their parents become roommates. Intimacy between parents creates a sense of security, modelling what healthy adult relationships should look like⁽³⁴⁾. So, when that tactile bond is absent, children often create weaker templates for trust and stability in their own relationships, which they may pass on to their own children, and so a generational cycle begins⁽³⁵⁾.

Sources: UN World Population Prospects 2022 (Total Fertility Rate) [G12]; ONS UK fertility statistics [G13]; OECD Family Database (cross-country comparatives) [G14].

And finally, zooming out to a societal level, we can see that birth rates are collapsing across most of the developed world. 1.5 in the UK, 1.6 in the US, just 0.7 in South Korea⁽³⁶⁾. Experts warn this means ageing populations, shrinking workforces, and mounting pressure on pensions and healthcare systems with long-term economic strain to follow⁽³⁷⁾.

I don’t want to be too hyperbolic here, but if the decline continues, and younger data suggests it will, the consequences are potentially quite serious for those left to pick up the pieces.

What Do We Do About It?

The good news is this isn’t out of our control, and you can probably guess what I am going to suggest… Yes… Have more sex!

Every couple that chooses to prioritise sex and closeness, rather than drift with the scattering herd, is part of the solution.

As a caveat, I am not suggesting this for couples dealing with serious relationship dysfunction. But in many marriages, the main issue is a lack of sex, and so the obvious solution is, quite often, more sex.

I have seen multiple couples do nothing more than decide to make sex a priority again. No big therapy breakthroughs, no drama, just a conscious choice. And the immediate results are less conflict, less stress, more affection, and more connection⁽³⁸⁾.

We really need to stop pretending sex doesn’t matter, because it does. And if you know it matters, which I know most of you reading do, then challenge the people around you who say it doesn’t, because they’re wrong.

Sex isn’t just a bonus for people who “deserve it”. It’s one of the things that keeps us healthy and fulfilled. It’s a beautiful life force that fuels love, generosity, art, music and creativity⁽³⁹⁾.

So, if sex continues to decline on a global scale, we will all suffer.

Are you affected by a Sexless marriage?

Do you need some guidance?

Book an Online Coaching Session with me here.

Laura How

Relationship Counsellor & Coach

Now, I am not saying sex is a magic cure-all. I know it won’t fix everything. But I do think a world in which men and women were more aligned and more intimate would be a better world for all of us.

So don’t be part of the problem. Be part of the solution.

That means choosing your partner over your phone. It means dealing with any relationship issues that are getting in the way. It means talking, touching, reconnecting. From there, make sex a regular, conscious habit; not a once-a-month event dependent on a long list of unachievable provisos.

Take your health seriously, so you’re not too exhausted or unwell to prioritise intimacy⁽⁴⁰⁾. And think about sex for what it is: a human need, as vital as affection, respect, or emotional closeness.

And finally, turn your back on divisive gender ideologies. They’re anti-life. Men and women are an incredible team that evolution has spent millions of years perfecting⁽⁴¹⁾. So, make the effort to turn toward each other and join forces. This all starts at home, with you, one couple at a time. A grass roots movement to heal the divide facilitated by the very thing that put us here in the first place.

I know this is easier said than done, so book a session with me if you need some support.

Thanks for reading. I’ll see you next week. In the meantime… to yourself and to others — tell the truth.

Recommended Reading About Sexless marriages

His Needs, Her Needs

‘This book will educate you in the care of your spouse,’ explains Dr Willard Harley. ‘Once you have learned its lessons, your spouse will find you irresistible, a condition that’s essential to a happy and successful marriage.’

This fresh and highly entertaining book identifies the ten most important needs within marriage for husbands and wives. It teaches you how to fulfil each other’s needs. Couples who find each other irresistible during the early years of their marriage may become incompatible if they fail to meet these central needs. According to Dr Harley, the needs of men and women are similar, but their priorities are vastly different.

Are you able to identify which of the following needs are his and which are hers? In what order would you place them? Admiration, Affection, An attractive spouse, Conversation, Domestic support, Family commitment, Financial support, Honesty and openness, Recreational companionship, Sexual fulfilment.

The Passionate Marriage

Passionate Marriage has long been recognized as the pioneering book on intimate human relationships. Now with a new preface by the author, this updated edition explores the ways we can keep passion alive and even reach the height of sexual and emotional fulfillment later in life. Acclaimed psychologist David Schnarch guides couples toward greater intimacy with proven techniques developed in his clinical practice and worldwide workshops. Chapters―covering everything from understanding love relationships to helpful “tools for connections” to keeping the sparks alive years down the road―provide the scaffolding for overcoming sexual and emotional problems. This inspirational book is sure to help couples invigorate their relationships and reach the fullest potential in their love lives.

The Sex-Starved Marriage

Bring the spark back into your bedroom and your relationship with gutsy and effective advice from bestselling author Michele Weiner Davis. It is estimated that one of every three married couples struggles with problems associated with mismatched sexual desire. If you want to stop fighting about sex and revitalize your intimate connection with your spouse, then you need this book. In “The Sex-Starved Marriage,” bestselling author Michele Weiner Davis will help you understand why being complacent or bitter about ho-hum sex might cost you your relationship. Full of moving first-hand accounts from couples who have struggled with the erosion of sexual desire and rebuilt their passionate connection, “The Sex-Starved Marriage” addresses every aspect of the sexual libido problem.

References

- Twenge, J. M., Sherman, R. A., & Wells, B. E. (2017). Declines in sexual frequency among American adults, 1989–2014. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(8), 2389–2401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0953-1

- Wellings, K., et al. (2019). Changes in, and factors associated with, frequency of sex in Britain: Evidence from three National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). BMJ, 365, l1525. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1525

- Muise, A., Schimmack, U., & Impett, E. A. (2016). Sexual frequency predicts greater well-being, but more is not always better. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(4), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615616462

- Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., & Rosen, R. C. (1999). Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA, 281(6), 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.6.537

- Brotto, L. A., & Luria, M. (2014). Sexual interest, desire, and arousal disorders in women. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 391–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185602

- Mercer, C. H., Tanton, C., Prah, P., Erens, B., Sonnenberg, P., Clifton, S., … Wellings, K. (2013). Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: Findings from Natsal-3. The Lancet, 382(9907), 1781–1794. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8

- Mitchell, K. R., Mercer, C. H., Ploubidis, G. B., Jones, K. G., Datta, J., Field, N., … Wellings, K. (2013). Sexual function in Britain: Findings from Natsal-3. The Lancet, 382(9907), 1817–1829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1

- Twenge, J. M., Sherman, R. A., & Wells, B. E. (2017). Declines in sexual frequency among American adults, 1989–2014. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(8), 2389–2401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0953-1

- Richters, J., Badcock, P. B., Simpson, J. M., Shellard, D., Rissel, C., de Visser, R. O., … Smith, A. M. A. (2014). Decline in partnered sexual activity in Australia. Sexual Health, 11(5), 472–479. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH14145

- Kontula, O., & Haavio-Mannila, E. (2009). The impact of aging on human sexual activity and sexual desire. Journal of Sex Research, 46(1), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490802624414

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster.

- Craig, L., & Mullan, K. (2010). Parenthood, gender and work-family time in the United States, Australia, Italy, France, and Denmark. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1344–1361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00769.x

- McDaniel, B. T., Coyne, S. M., & Holmes, E. K. (2012). New mothers and media use. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(7), 1509–1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0918-2

- Wright, P. J., Tokunaga, R. S., & Kraus, A. (2016). A meta-analysis of pornography consumption and actual acts of sexual aggression. Journal of Communication, 66(1), 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12201

- Travison, T. G., Araujo, A. B., Kupelian, V., O’Donnell, A. B., & McKinlay, J. B. (2007). Contributions of aging, health, and lifestyle to serum testosterone decline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 92(2), 549–555. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-1859

- Feldman, H. A., Longcope, C., Derby, C. A., Johannes, C. B., Araujo, A. B., Coviello, A. D., … McKinlay, J. B. (2002). Age trends in serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 87(2), 589–598. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.87.2.8201

- NHS Digital. (2022). Prescriptions for antidepressants in England. https://digital.nhs.uk

- Pratt, L. A., Brody, D. J., & Gu, Q. (2017). Antidepressant use among persons aged 12 and over: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief, 283. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db283.htm

- Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., & Han, B. (2016). Depression in adolescents and young adults: Trends and treatment. Pediatrics, 138(6), e20161878. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1878

- Montejo, A. L., Montejo, L., & Baldwin, D. S. (2018). Severe mental disorders, psychotropics, and sexual health. World Psychiatry, 17(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20492

- Cherlin, A. J. (2009). The Marriage-Go-Round. Vintage.

- Waite, L. J., & Gallagher, M. (2000). The Case for Marriage. Broadway Books.

- Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (2008). Habits of the Heart. University of California Press.

- Regnerus, M., & Uecker, J. (2011). Premarital Sex in America. Oxford University Press.

- Muise, A., Schimmack, U., & Impett, E. A. (2016). Sexual frequency predicts greater well-being, but more is not always better. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(4), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615616462

- Manne, K. (2018). Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny. Oxford University Press.

- Farvid, P., Braun, V., & Rowney, C. (2017). Women, heterosexual casual sex and the sexual double standard. Journal of Gender Studies, 26(5), 544–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1150818

- Impett, E. A., Muise, A., & Peragine, D. (2014). Sexuality in the context of relationships. In D. L. Tolman & L. M. Diamond (Eds.), APA Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 269–315). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14193-009

- Twenge, J. M., Sherman, R. A., & Wells, B. E. (2017). Declines in sexual frequency among American adults, 1989–2014. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(8), 2389–2401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0953-1

- Muise, A., Schimmack, U., & Impett, E. A. (2016). Sexual frequency predicts greater well-being, but more is not always better. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(4), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615616462

- Yeh, H. C., Lorenz, F. O., Wickrama, K. A. S., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H. (2006). Sexual satisfaction, marital quality, and marital instability at midlife. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(2), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.339

- Brody, S. (2010). The relative health benefits of different sexual activities. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(4), 1336–1361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01677.x

- Lindau, S. T., & Gavrilova, N. (2010). Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health. BMJ, 340, c810. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c810

- Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1269–1287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01269.x

- Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2010). Marital Conflict and Children: An Emotional Security Perspective. Guilford Press.

- OECD Family Database. (2023). Fertility rates. https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm

- United Nations, DESA, Population Division. (2022). World Population Prospects 2022. https://population.un.org/wpp/

- Muise, A., Impett, E. A., Kogan, A., & Desmarais, S. (2013). Keeping the spark alive: Meeting a partner’s sexual needs sustains desire. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(3), 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612457185

- Waite, L. J., & Gallagher, M. (2000). The Case for Marriage. Broadway Books.

- Laumann, E. O., Nicolosi, A., Glasser, D. B., Paik, A., Gingell, C., Moreira, E., & Wang, T. (2005). Sexual problems among adults 40–80: Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. International Journal of Impotence Research, 17(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijir.3901250

- Buss, D. M. (2017). Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind (6th ed.). Routledge.

Graph References

- [G1] Johnson, A. M., Mercer, C. H., Erens, B., Copas, A. J., McManus, S., Wellings, K., … & Field, J. (2013). Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain (Natsal-3). The Lancet, 382(9907), 1781–1794. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8

- [G2] YouGov. (2020). How often are Britons having sex? https://yougov.co.uk/topics/health/articles-reports/2020/02/12/how-often-are-britons-having-sex

- [G3] Johnson, A. M., Wadsworth, J., Wellings, K., & Field, J. (2001). Sexual behaviour in Britain (Natsal-2). The Lancet, 358(9296), 1835–1842. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06886-6

- [G4] Twenge, J. M., Sherman, R. A., & Wells, B. E. (2017). Declines in sexual frequency among American adults, 1989–2014. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(8), 2389–2401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0953-1

- [G5] Travison, T. G., Araujo, A. B., O’Donnell, A. B., Kupelian, V., & McKinlay, J. B. (2007). Population-level decline in serum testosterone. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 92(1), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-1375

- [G6] Shi, Z., Aitken, D., Zhao, Y., et al. (2020). Declining testosterone in adolescent and young adult males. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry, 57(3), 282–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004563219899576

- [G7] Chodick, G., et al. (2020). Secular trends in testosterone testing/treatment. BJU International, 125(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14950

- [G8] NHS Business Services Authority. (2022). Medicines Used in Mental Health – England 2015/16 to 2021/22. https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/medicines-used-mental-health-report

- [G9] NHS England / NHSBSA. Prescription Cost Analysis (England) – time-series tables. https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/prescription-data/dispensing-data/prescription-cost-analysis-pca-data

- [G10] Brody, D. J., Gu, Q., & Simpson, S. M. (2020). Antidepressant use among adults, 2015–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 377. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db377.htm

- [G11] Taylor, E., Turnbull, S., & Kapur, N. (2019). Trends in antidepressant prescribing to children and adolescents in England: 2005–2017. BMJ Open, 9(6), e026905. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026905 (UK child/adolescent prescribing roughly doubled since mid-2000s).

- [G12] United Nations DESA, Population Division. (2022). World Population Prospects 2022 (TFR). https://population.un.org/wpp/

- [G13] Office for National Statistics. (2023). Births in England and Wales: 2022. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths

- [G14] OECD. (2024). Family Database – SF2.1: Fertility rates. https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm